A.4.1 Rotational motion equations

Definitions of key terminologies

Symbol | Definition | SI units | Relationship to linear quantities | |

Angular displacement | Change in the angle as the objects moves

(final angle - initial angle) | |||

Angular Velocity | The rate (t) of change of angular displacement

| |||

Angular Acceleration | The rate of change of angular velocity |

•

Notice that all variables that describe angular motion have similar analogous variables that describe linear motion.

•

All the suvat equations can be rewritten using angular variables

A.4.2 Torque

Torque

•

If all linear variables have a rotational analogue it follows that force used in linear equations will also have a rotational analogue

•

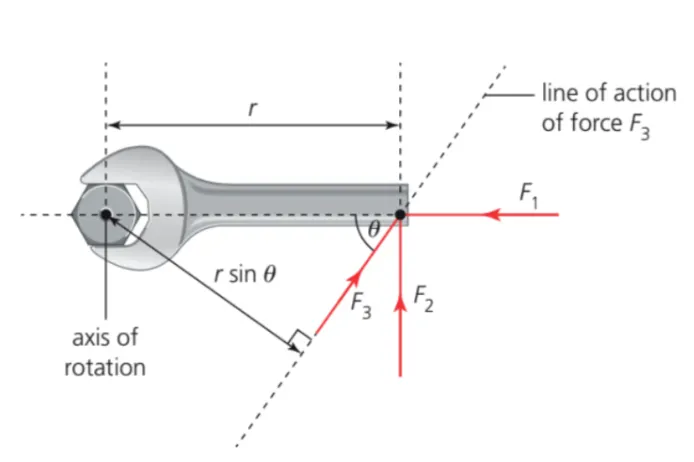

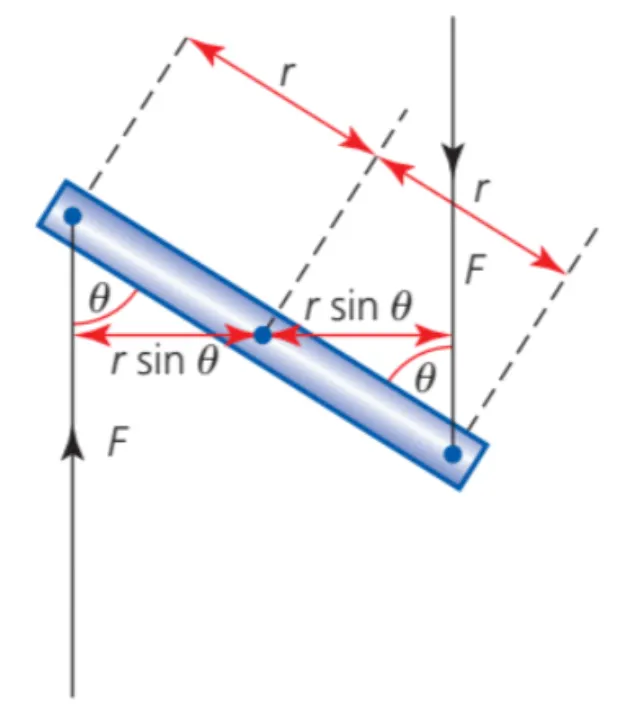

Torque is used the same way in rotational equations and is defined as the product of the tangential force times the distance from the point the force is applied to the center of rotation.

◦

•

Newton’s laws of motion apply to torque the same way they apply to forces

◦

◦

◦

For every torque, there is an equal and opposite torque

•

Notice that Newton’s second law requires a quantity that is similar to mass, but that can be used in rotational motion equations. This quantity is called moment of inertia and is discussed below.

•

Be careful when calculating the torques since torque values depend on the distance to the center of rotation, rotating (or sometimes called pivoting) about a different axis will result in different values of torque.

Torque equilibrium

•

Torque equilibrium occurs when the net torque is zero and the angular acceleration is also zero.

•

The axis of rotation must be given if an object rotates, but if an object is in rotational equilibrium (i.e. is not rotating) then you are free to choose any point as the axis of rotation.

•

Although any point can be used, usually the pivot point (axis of rotation) is set to coincide with the position of an unknown force or torque because it simplifies the equation (since the distance being zero results in that unknown variable being removed from the equation)

•

In the same way as forces are set as positive in one direction and set as negative in the other direction, torque in opposite directions have opposite signs.

◦

The difference is that for linear forces the directions are usually up/down or left/right, while for torque the two directions are clockwise or counter-clockwise (or anti-clockwise).

◦

Which direction is positive or negative doesn’t matter, just makes sure that once you pick a positive direction, all torques must follow the same rule (this includes the net torque direction!).

A.4.3 Center of mass

Center of Mass

•

Objects are ideally modeled as points and all of their mass is assumed to exist at that one point. That point is called the center of mass.

•

For symmetrical objects such as squares, rectangles, cubes, rods, circles and spheres; the center of mass is assumed to be at the exact center of those objects.

•

The force of gravity is also assumed to be exerted at the center of mass (which is necessary when attempting to calculate the torque due to gravity.

•

When a force is exerted at the center of mass or in a radial direction (in a direction towards or away from the center) of a free object the object (meaning it's not pinned down or forced to rotate along another axis) will simply accelerate linearly.

•

If a force is exerted tangentially (perpendicular to the center) on a free object, it will experience angular acceleration.

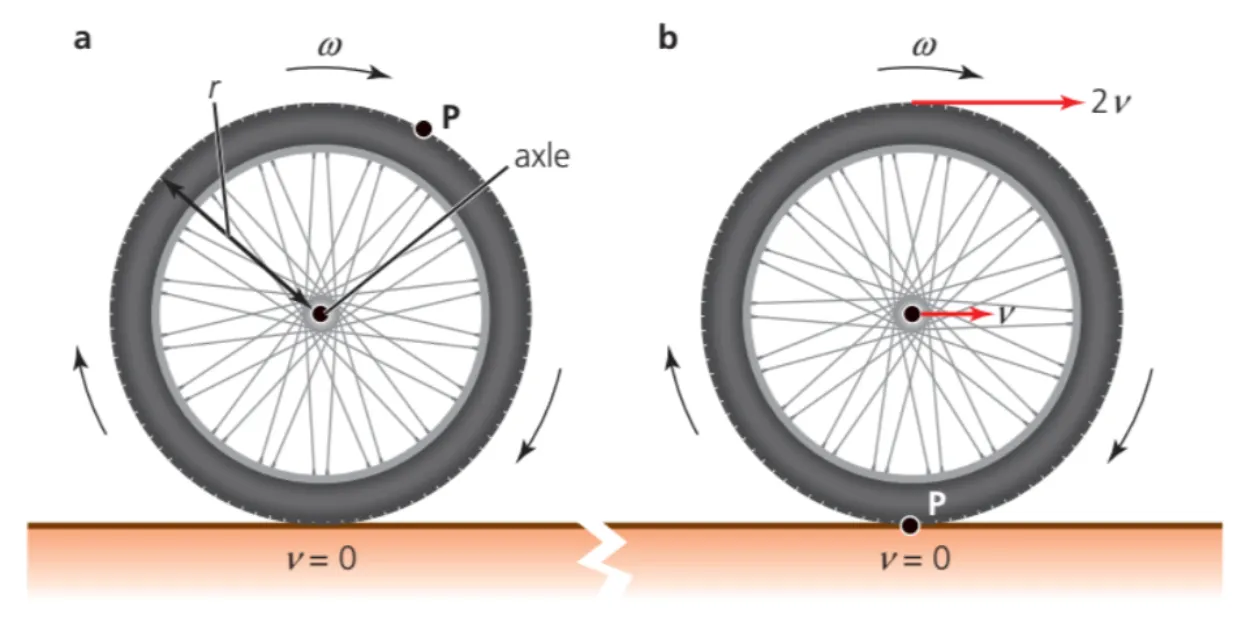

A.4.4 Moment of inertia

Moment of inertia

•

The term moment in physics means that it is related to rotation.

•

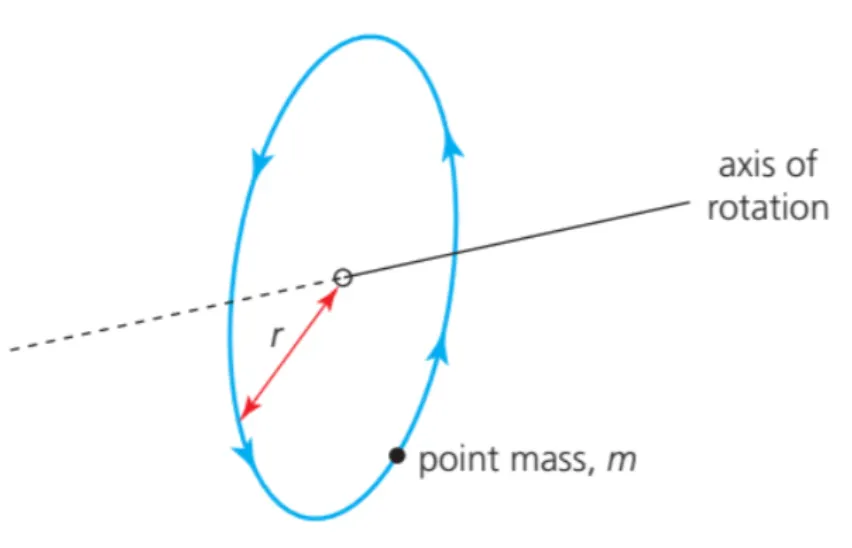

Inertia, in this case, refers to an object's resistance to acceleration. In linear equations inertia refers to the mass of an object, but for rotational motion an object's resistance to angular acceleration is referred to as the moment of inertia, and it occupies the same role as mass in rotational equations

•

The moment of inertia of a single point object is defined as:

•

If an object is composed of several point objects connected to each other, the total moment of inertia is the sum of the individual moments of inertia

•

Be careful using these equations because the moment of inertia depends on the distance to the axis of rotation. If you rotate an object around a different axis, then all the values for moments of inertia will also change.

•

The calculation of the moment of inertia of point masses is straight forward, but real life objects are not really points. Objects in real life have volumes and their masses distributed across their bodies.

•

For example, although it is tempting to use

•

mr2 to calculate the moment of inertia of a sphere, remember that not all the mass is at exactly a distance of r from the centre. Most of the mass of a solid sphere will be closer to the center than r.

•

Thus the moment of inertia of any real object will always be less than or equal to mr2.

•

The exact value of moment of inertia for objects requires calculus to calculate so for the purposes of this course the moments of inertia will be given.

•

The only 3-dimensional objects for which the moment of inertia is exactly mr2 are wheels and hollow cylinders with axis of rotations through the centre, since all the mass of those objects is at the same distance r from their centres.

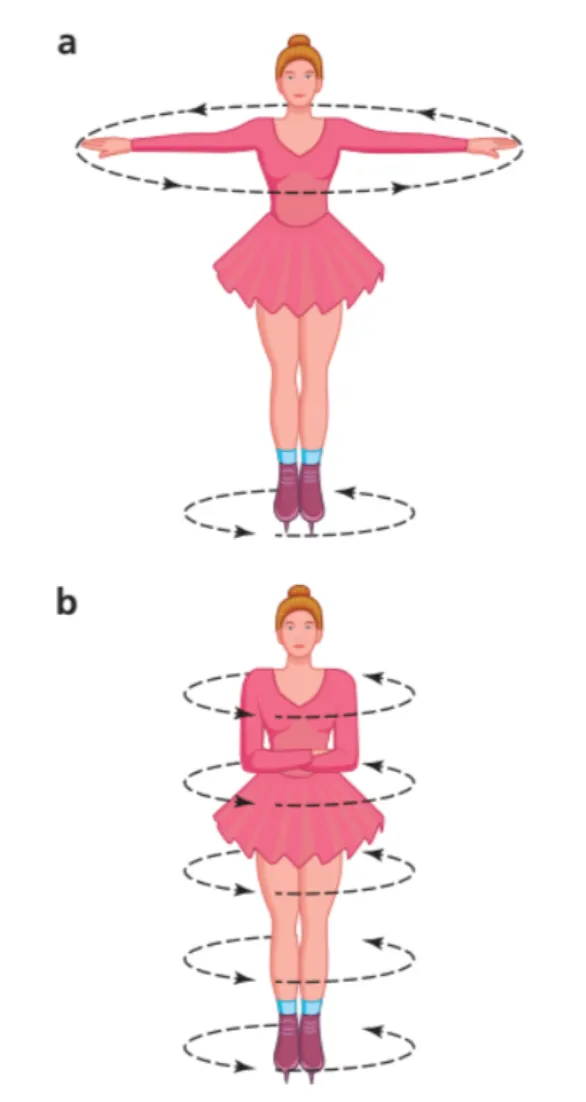

A.4.5 Angular momentum

Angular momentum

•

Angular momentum is analogous to linear momentum.

•

While linear momentum is , angular momentum is

•

Angular momentum is conserved the same way linear momentum is conserved

•

Remember that the sign (positive/negative) for angular momentum also depends on if it is clockwise/counter-clockwise the same as torque.

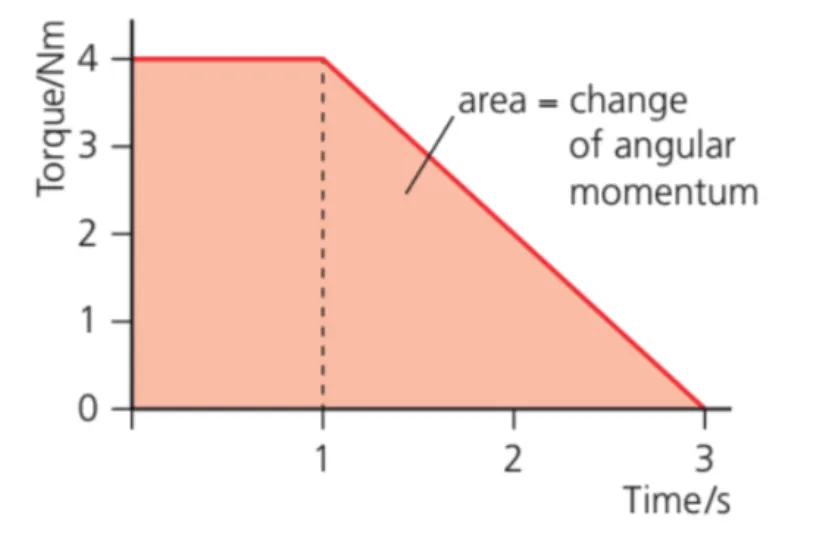

Angular impulse

•

Angular impulse, , is defined as the change in angular momentum, .

•

Angular impulse can be found in one of three ways

◦

As a result of the change of angular velocity and constant moment of inertia

▪

◦

As a result of change of moment of inertia and constant angular velocity

▪

◦

As a result of torque applied over a time .

▪

▪

A.4.6 Rotational energy

Rotational Energy

•

For rotational motion, work is found in terms of angular displacement and torque instead of force and displacement, but both equations are equivalent and yield the same result

◦

•

Rotational kinetic energy

◦

◦