B.3.1 Avogadro constant, Pressure, and Gas Laws

Molar Concept Rules

Terminology | Definition / Equation |

mole (mol) | amount of the substance having the same number of neural atoms as 12g of carbon-12 |

Avogadro constant () | number of atoms in 12g of carbon-12

atoms / particles / molecules |

molar mass () | mass of 1 mol of a substance

|

pressure () | normal force per unit area

SI Unit: |

Gas Laws

•

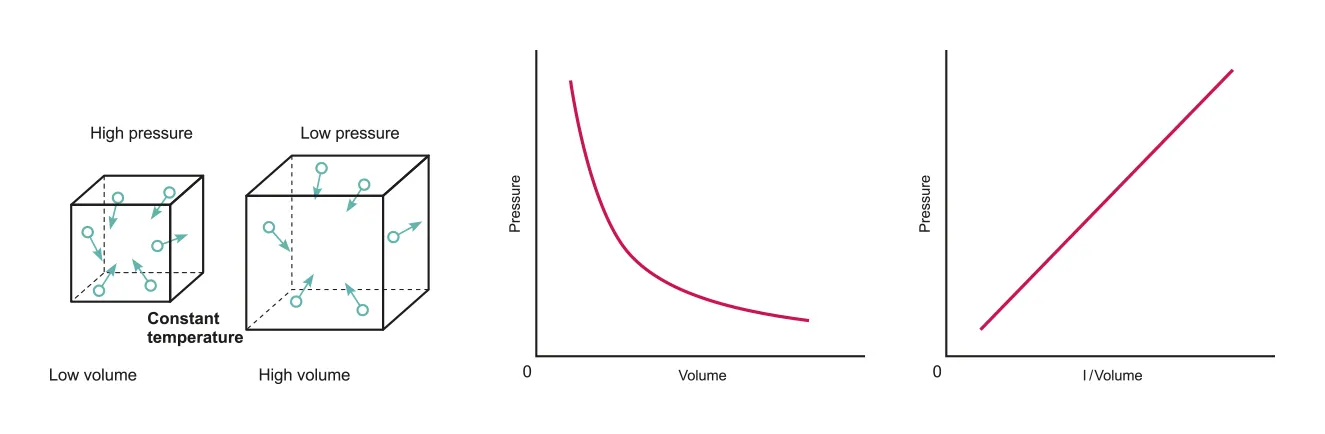

Boyle’s Law : Pressure of a gas of fixed mass and at a constant temperature is inversely proportional to its volume

◦

Isothermal process: temperature is constant

◦

Sealed or closed system: mass is constant

B.3.1-1 Diagram of particles in high and low pressure and graph that represents the relationship between volume and pressure

•

This means that the product of p and V is always constant

•

Charles’s Law : Volume of a gas of fixed mass and constant pressure is directly proportional to its temperature

◦

Isobaric: constant pressure

◦

Closed system: fixed mass

•

Which means V divided by T is always constant

B.3.1-2 Diagram of particles at low temperature and high temperature and graph representing relationship between volume and temperature

•

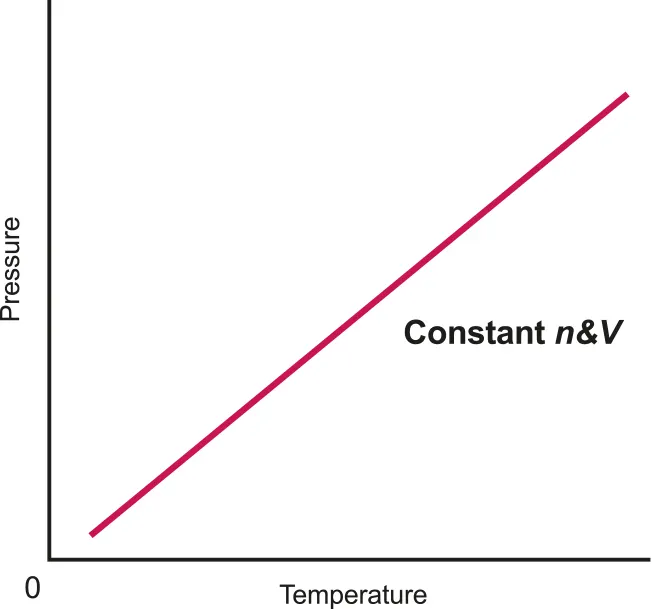

Gay Lussac’s Law : Pressure of a gas of fixed mass and volume is directly proportional to its temperature

◦

Isochoric or Isovolumetric: constant volume

◦

Closed system: fixed mass

•

Which means p divided by T is always constant

B.3.1-3 Graph that representing the relationship between pressure and temperature

•

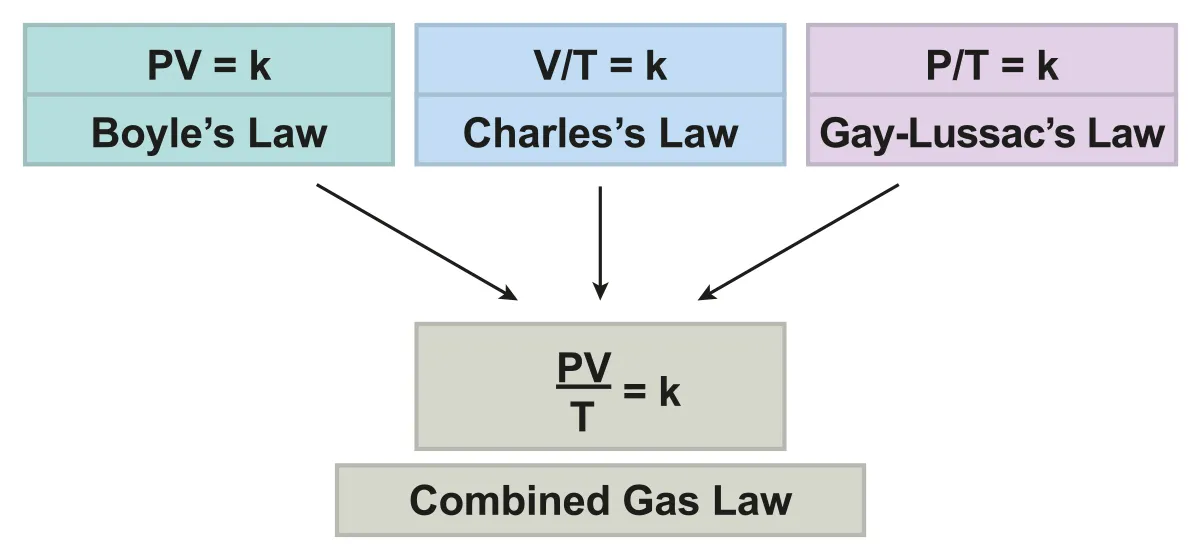

Combined Gas Laws : three gas laws can be combined into one

is always constant

B.3.1-4 Diagram that shows how Combined Gas Law is constructed

•

Ideal Gas Law :

◦

For a gas at constant temperature and pressure, the number of moles is directly proportional to the volume of the gas

◦

Combining three laws, single constant R is given

◦

So, Ideal Gas Law equation can be expressed as:

•

This equation requires that the number of molecules be express as moles since the units of the ideal gas constant also includes moles.

•

If the number of molecules is used, the Boltzmann constant must replace the ideal gas constant

•

This implies that both the ideal gas constant and the Boltzmann constant are related by the equation

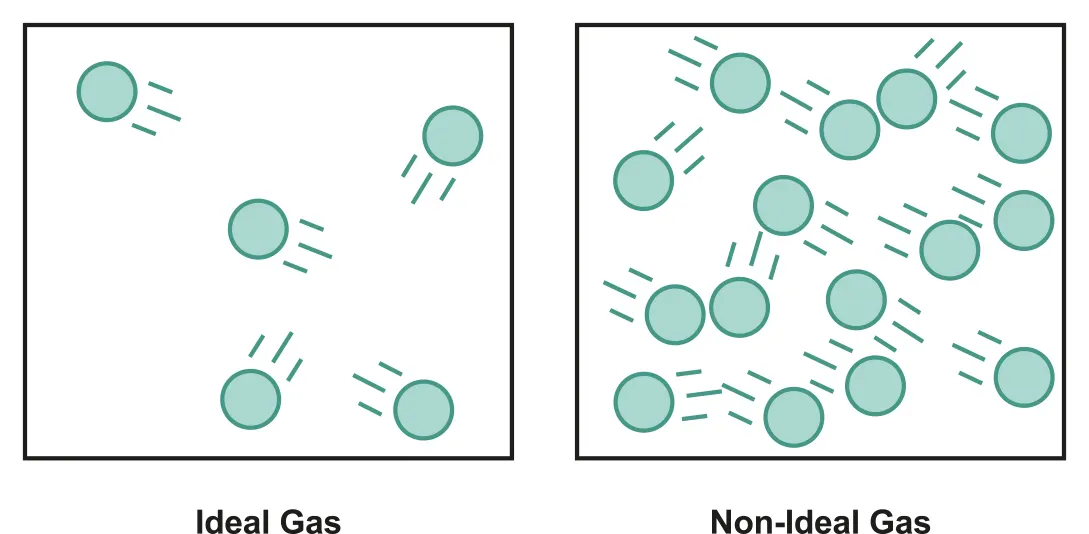

B.3.2 Differences between real and ideal gasses

Ideal gas assumptions:

•

Molecules are point particles with negligible volume compared to volume of gas

•

Zero intermolecular forces except when collisions occur

•

Perfectly elastic collisions between molecules and with the container walls

•

The collision time is negligible compared to the time between collisions

•

The velocity and direction of the molecules is random

•

Molecules obey Newton’s laws of motion

Differences between real and ideal gasses

•

The volume of molecules of real gasses is NOT zero.

◦

This doesn’t make much of a difference at low densities, but real gasses cannot be compressed to near zero volume

◦

At some point applying additional pressure on a gas will not further compress it as predicted because the atoms are ‘touching’ each other and the volume of the molecules is approximately equal to the volume of the container

•

Real gasses do experience some intermolecular force.

◦

At high enough temperatures, these forces are negligible since the high velocities means that small forces do not make much of a difference.

◦

At lower temperatures, the attractive intermolecular forces between the molecules will cause them to ‘stick’ together. This causes a change of state from a gas to a liquid (liquefaction or condensation) or in some cases directly from a gas into a solid (gas deposition).

⇒ Real gasses are closest to ideal gasses at sufficiently high temperatures and low enough pressures.

∵ Such condition allows relatively large distances between molecules and high speed due to high T overcome interactions.

B.3.2-1 2D diagram of ideal gas and non-ideal gas particles

B.3.3 Kinetic model of an ideal gas

Kinetic molecular theory of an ideal gas

•

Collision with the wall leads to the concept of pressure

B.3.3-1 Diagram of gas state particles

•

When molecules of a gas collide with the walls of a container, impulse is transferred to the walls of the container

•

The force on the walls of the container depends on the frequency of the collisions and the average impulse transferred by each collision.

•

Since the pressure of the gas is proportional to the force, increasing the frequency of collisions per unit or increasing the impulse transferred by each collision will increase the pressure.

•

Increasing the temperature of the gas of fixed mass and volume will increase the pressure of the gas by

◦

Increasing the average KE and therefore the average velocity each molecule and increases the average impulse transferred to the wall by each collision

◦

Decreases the average amount of time between collisions since a faster moving molecule will require less time to travel to the other side of the container and back again

•

Increasing the number of molecules of a gas of fixed volume and constant temperature will increase pressure of the gas by:

◦

Increasing the number of collisions per unit area which increases the total impulse transferred to the wall, increasing the force, and the pressure

•

Decreasing the volume of a gas of fixed mass and constant temperature will increase pressure of the gas by:

◦

Decreases the average amount of time between collisions since a faster moving molecule will require less time to travel to the other side of the container and back again

◦

Increasing the density of molecules which Increases the number of collisions per unit area which increases the total impulse transferred to the wall, increasing the force, and the pressure

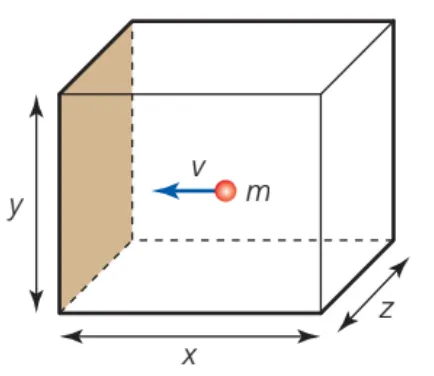

Pressure in terms of rms Velocity

•

The impulse of a single molecule colliding with the wall of the container is

◦

where m is the mass of a single molecule and is the rms velocity along a single axis

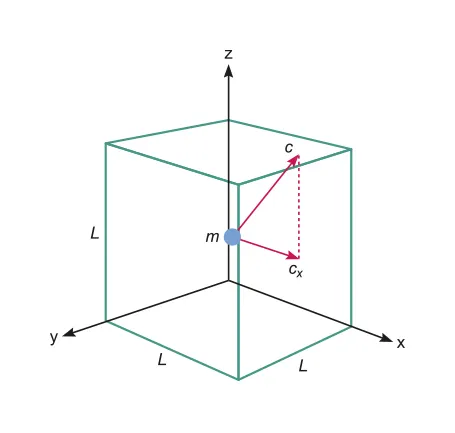

The time t between collisions in a cubic container with sides l is since the molecule must move a distance of in order to hit the same wall again

•

The kinetic energy of the molecule is the sum of the kinetic energy of each axis.

◦

B.3.3-2

•

So and since the average velocity is the same in all three axes

•

•

The force caused by the collision of one molecule on the wall is:

◦

•

The total force on the wall by a gas with molecules is

◦

•

The pressure in the container is defined as the force per unit area due to all the molecules of the gas:

◦

•

The area of one face of the container is so:

◦

•

The density of the gas in the mass of the gas over the volume of the gas , therefore

◦

•

Finally, since , in general the pressure of a container in terms of the rms velocity is:

◦

◦

where is the density of the gas and is the rms velocity of the molecules

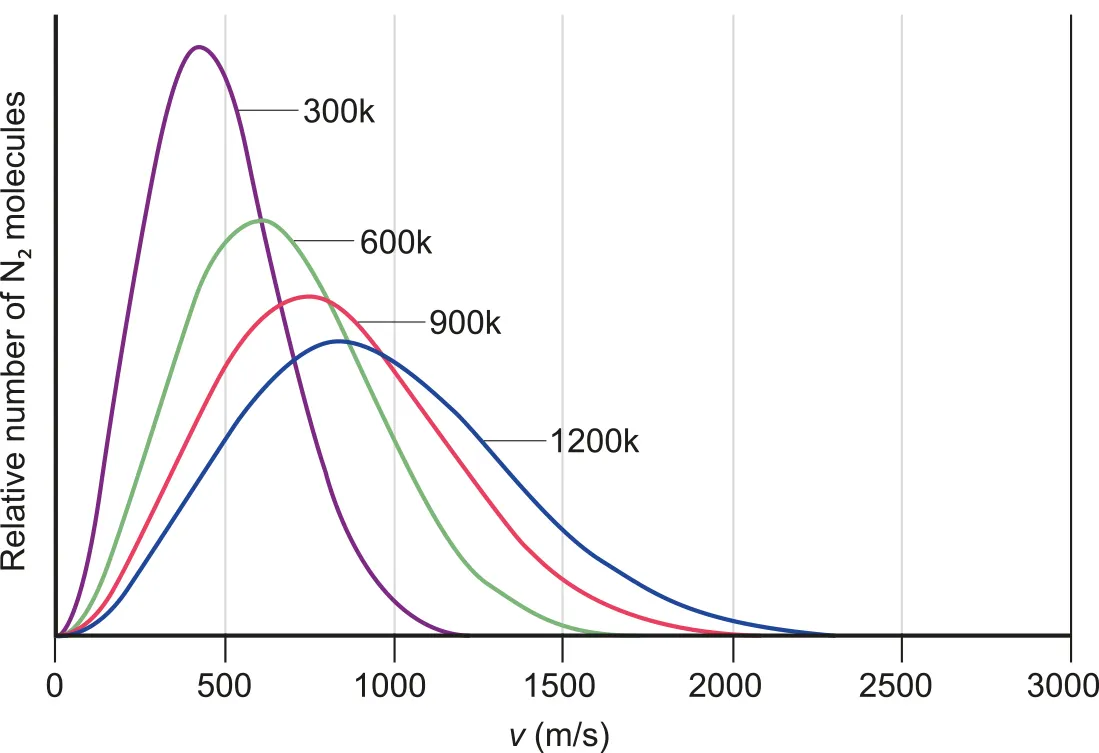

Average Kinetic Energy of a Gas Particle

•

Gas molecules have a random distribution of velocities.

B.3.3-3 Multiple graphs of molecules velocity in different temperatures

•

Increase in temperature →

◦

Lower fraction of molecules move at lower speeds

◦

Greater fraction of molecules move at higher velocities.

B.3.3-4 Diagram represents the velocity of molecules in volume

Internal Energy of a Gas

•

Internal energy

•

Ideal gasses have zero potential energy because the intermolecular force is zero (and work is force times displacement in the same direction);

•

Total internal energy is only dependent on the total random KE