B.1.1 Molecular theory of solids, liquids and gases

Understanding: Properties of the three states of matter considered in physics

Particle Model of Matter:

B.1.1-1 Diagram of 3 main states

•

Model that attempts to explain the properties of the three states of matter

◦

Particles are assumed to be small spheres

Properties of a Solid:

•

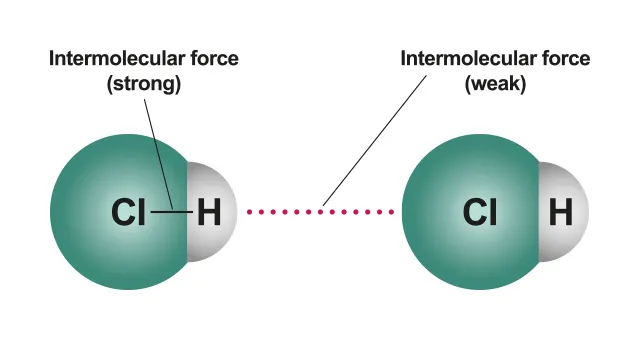

Atoms are fixed in place by a strong force (or bond) between each other. → Strong intermolecular force between atoms (fixed structure)

•

This force prevents the atoms from separating and keeps the volume and shape constant

•

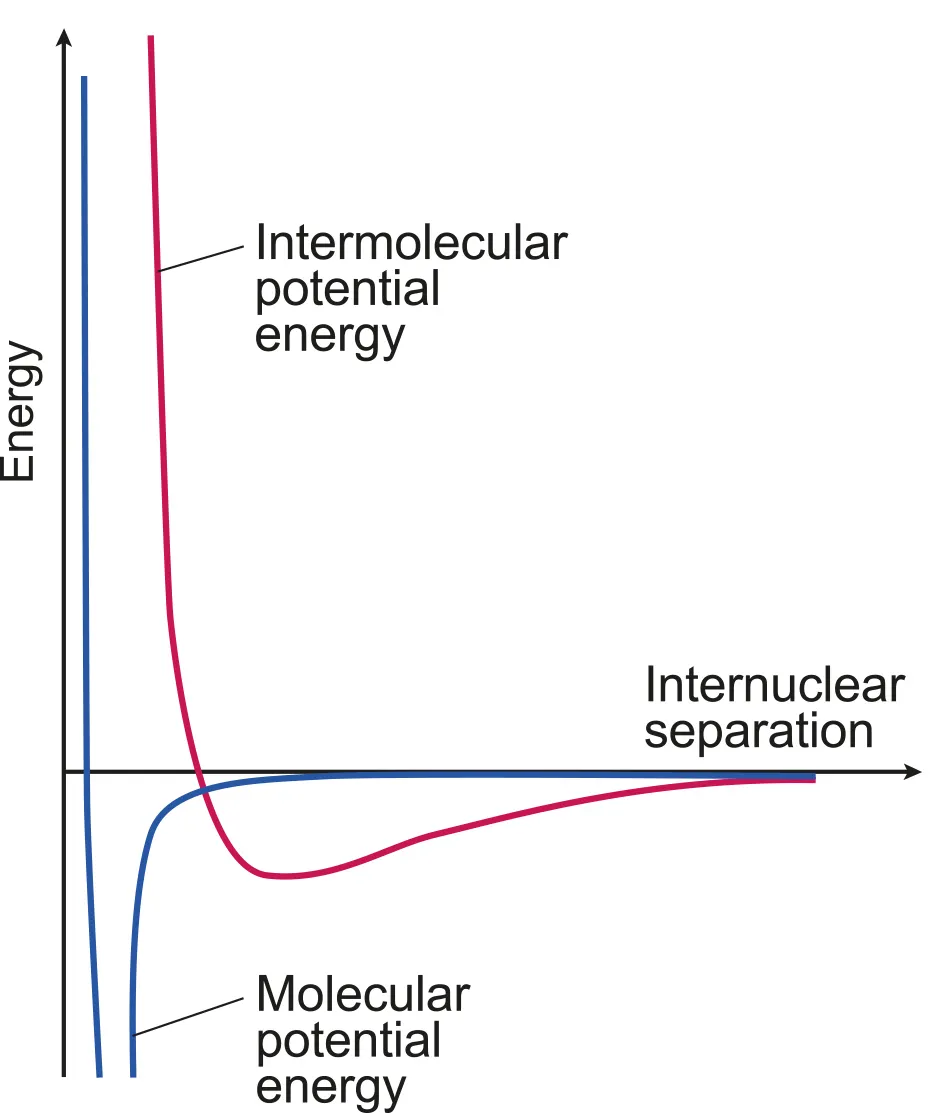

Greater distances → attractive force (energy released during bond formation), shorter distances → repulsive force

•

The attractive intermolecular force between the atoms in the solid means energy is required to move atoms away from each other and energy is released when the atoms move closer

•

Lowest potential energy

•

This intermolecular force between the atoms is referred to as a bond because it keeps the atoms in place.

•

‘Breaking the bonds” refers to the act of moving atoms away from each other. Since this means there is a force and a displacement, breaking the intermolecular bonds between atoms requires work to be done (energy).

•

Bonds in solids require the highest amount of energy to break because the forces between solid atoms are the strongest.

B.1.1-2 Diagram of intermolecular force

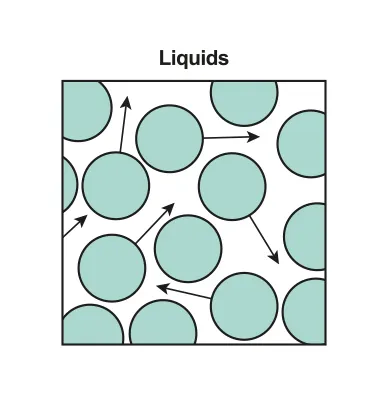

Properties of a Liquid:

•

Liquids also maintain a roughly constant volume which means the average distance between the atoms is also roughly constant.

•

An intermolecular force between the atoms in liquid is required to keep the average distance the same.

•

Atoms in a liquid are able to flow and change shape which means that although the average distance between atoms is constant, the atoms are able to move past each other.

•

When atoms in a liquid ‘flow’, the bonds between the atoms are broken and reformed.

•

This implies that the intermolecular forces between atoms in a liquid are much weaker than the intermolecular forces between atoms in a solid (the force between the atoms in a solid are so strong that they are fixed in place).

•

Less energy required to break bonds, meaning liquids are a higher energy state

•

Higher density than gas, but lower density than solid

B.1.1-3 Diagram of liquid state particles

Properties of a Gas:

•

Intermolecular forces between the molecules in a gas are negligible

•

The lack of intermolecular forces implies that the molecules in a gas are free to move away from each other and expand without additional energy.

•

In solids and liquids the intermolecular forces (bonds) prevent the atoms from separating (so they can’t expand) and neither can they contract because all the atoms are so close to each other they are basically ‘touching’ each other (cannot be compressed).

•

Distance between gas molecules is very large compared to the size of the molecules so gasses have low density and are easily compressed

•

Particles in a gas move in random directions and at random speeds

•

All molecules of all substances are constantly in motion so they collide with each other or with the walls of the container

Properties comparison between states

States of Matter | Solid | Liquid | Gas |

Particle arrangement | fixed structure (lattice) | random | random |

Space between particles | negligible | negligible | Very large |

Intermolecular forces | very strong | strong (weaker than solids) | negligible |

Particle movement | vibrate in fixed position | ‘flow’ past each over by breaking and forming bonds | Move freely |

Particle potential energy | very low | low (higher than solids) | zero |

Substance shape | fixed | not fixed | not fixed |

Substance volume | fixed | fixed | not fixed |

Substance density | high | high | very low |

B.1.2 Temperature and Internal energy

Understanding: The temperature of a substance is directly proportional to the average kinetic energy of its particles.

Energy in substances

•

When calculating the total energy in a substance only potential energy and kinetic energy need to be considered.

•

Potential energies of atoms depend ONLY the intermolecular forces between the atoms (bonds) and therefore also depend on the state (i.e. solid, liquid, gas)

•

The kinetic energy of atoms depends ONLY on their temperature

◦

The atoms in a solid, a liquid, and a gas at the same temperature will all have EXACTLY the same amount of kinetic energy

Temperature

•

Temperature is an indirect measurement of average random kinetic energy in the atoms in a substance

◦

All the atoms still have different random velocities, it's just the average kinetic energy that depends on temperature

◦

Random KE only when the atoms move in different random directions and is completely unaffected by the linear KE

▪

all the atoms moving in the same direction doesn’t increase the random KE

▪

throwing a baseball increases its linear KE but not it’s random KE so the temperature doesn’t increase either

•

Potential energy (PE) in the bonds (forces) between particles does NOT affect temperature

•

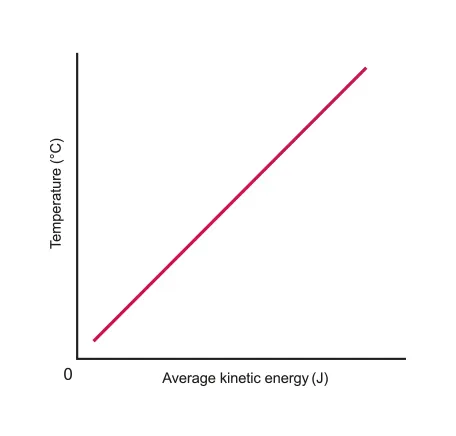

Temperature is directly proportional to the average kinetic energy (KE) of particles

◦

The average KE of the particles depend only on the absolute temperature in Kelvin regardless of the state

B.1.2-1 Graph representing relationship between average KE of particles and temperature

•

Units: Celsius or Kelvin (K)

•

Kelvin temperature can be calculated by Celsius temperature

•

There is zero average KE (no random motion) at absolute zero (0 Kelvin)

•

KE is NOT zero at 0 degrees celsius

Calculating average KE of particles with temperature

•

Average KE can be calculated with temperature of objects

•

In this calculation Bolstman constant is used for this calculation

Measuring Temperature

•

KE of individual particles cannot be measured; so we use indirect measurement methods.

•

Principle of mercury thermometers: the volume liquid mercury metal increases linearly with temperature, thus changes in volume can be used to measure temperature

◦

Normally, volume of liquid change due to the temperature rise is so small so its negligible except abnormal cases

◦

Thermometer calibration for accuracy: volumes at freezing and boiling temperatures of water are recorded

B.1.2-2 Example diagram of temperature measurement

•

Making a thermometer requires the use of two known temperatures.

◦

a celsius thermometer is dipped in ice water since it is at a stable temperature of 0℃

◦

the height of the mercury is marked and labeled 0℃, but it is still impossible to measure the temperature with only one tick mark at zero.

◦

the thermometer is dipped into boiling water (at a stable and constant 100℃)

◦

marking the thermometer at 100℃ makes it possible to divide the space between 0 and 100℃ into one hundred equally spaced units and measure any temperature in between

Internal Energy and Heat

•

Internal Energy : the sum of the total random kinetic energy and the total intermolecular potential energy of the particles within the substance

•

When thermal energy is transferred to a substance it can cause an increase in the random KE or an increase in PE, but not both at the same time

◦

Increase in the random KE of a substance increases the average KE of the particles so the temperature increases

◦

Increase in the PE of a substance means the intermolecular bonds between particles are broken and so the distance between particles increases. This causes a change of state from a solid to a liquid (or from a liquid to a gas).

•

So, only an increase in average KE of the particles can result the change in temperature

•

Change in PE of substance will not result any change in temperature

•

Heat = change in internal energy (i.e. transfer of thermal energy)

◦

Internal energy = U, Heat = Q = ΔU

B.1.3 Specific heat capacity, Phase change and Specific latent heat

Understanding: Specific heat capacity, specific latent heat, and heat equations

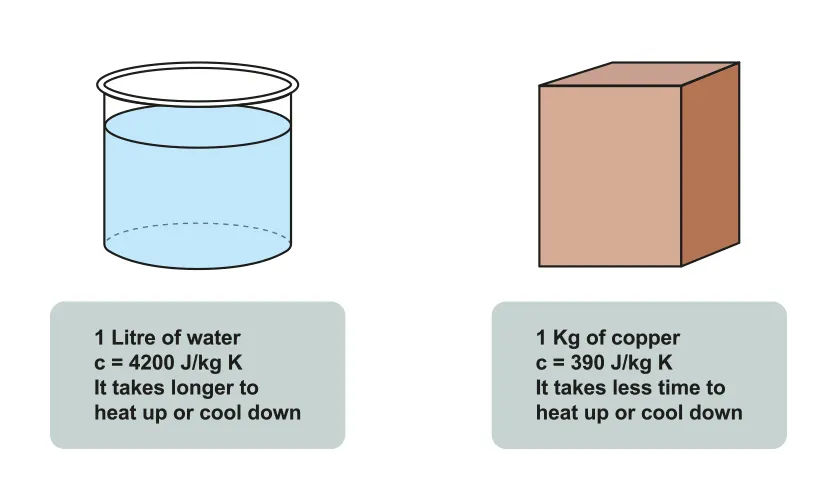

Specific Heat Capacity: thermal energy required to change the temperature of one unit of mass of a substance by one unit of temperature

B.1.3-1 Diagram of water and copper with specific heat capacity notated

•

Temperature increase requires energy as the average KE of particles is increased.

•

Every substance requires different amounts of energy to increase temperature by 1K.

•

Units:

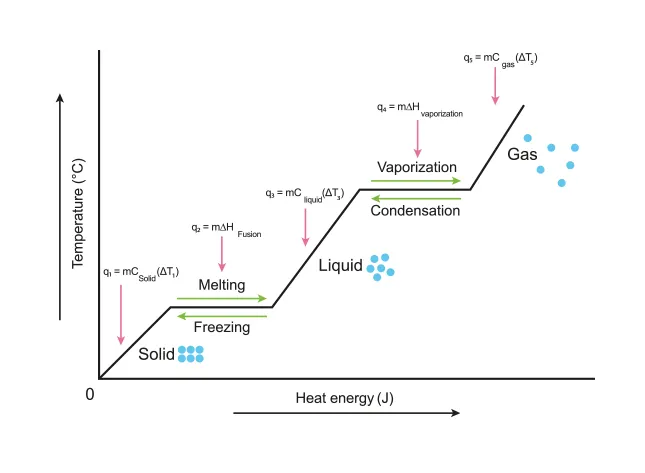

Phase Change: change of state of matter of a substance

•

A phase change represents a change in particle behaviour arising from a change in energy at constant temperature

•

Adding heat increases the average KE (thus temperature) of a substance

•

At melting points, additional energy is required to break the bonds (PE) of the solid, rather than increasing the KE

◦

Same concept applied to liquid → gaseous state process

•

Reverse processes (gas → liquid; or liquid → solid) release energy

Specific Latent Heat: the energy required to change the state of a substance per unit mass

Substance | Specific Latent Heat of Fusion (kJ/kg) | Melting Temperature (°C) | Specific Latent Heat of Vaporization (kJ/kg) | Boiling Temperature (°C) |

Water | 334 | 0 | 2,260 | 100 |

Ethanol | 109 | -114 | 840 | 78 |

Aluminium | 395 | 660 | 10,550 | 2,467 |

Lead | 23 | 327 | 850 | 1,740 |

Copper | 205 | 1,078 | 2,600 | 5,190 |

Iron | 275 | 1,540 | 6,300 | 2,800 |

Phase Change Diagram

B.1.3-2 Graph representing temperature change during state changes

•

During the phase change, temperature does not change

◦

Because heat energy supplied to the object is used to increase the PE of the substance (break intermolecular bonds between particles)

•

Melting temperature

◦

In order to change from a solid to a liquid, the molecules in the substance need enough KE to break the bonds

◦

At the melting temperature, some of the fastest molecules in the solid have almost enough KE to break free from the solid bonds and become a liquid.

◦

Since the fastest molecules in the solid escaped (melted) to become a liquid, the average KE energy of the solid decreases slightly

◦

Even though the molecule that escaped the solid had a very high KE compared to the average, some of that KE is used to break the bonds so it is approximately average KE and so the temperature of the liquid does not change.

•

Boiling temperature

◦

In order to change from a liquid to a solid, the molecules in the substance need enough KE to break the bonds

◦

At the boiling temperature, some of the fastest molecules in the liquid have almost enough KE to break free from the liquid bonds and become a gas.

◦

Since the fastest molecules in the liquid escaped (boiled) to become a gas, the average KE energy of the liquid decreases slightly

◦

Even though the molecule that escaped the liquid had a very high KE compared to the average, some of that KE is used to break the bonds so it is approximately average KE and so the temperature of the gas does not change.

Thermal Equilibrium of Mixtures

•

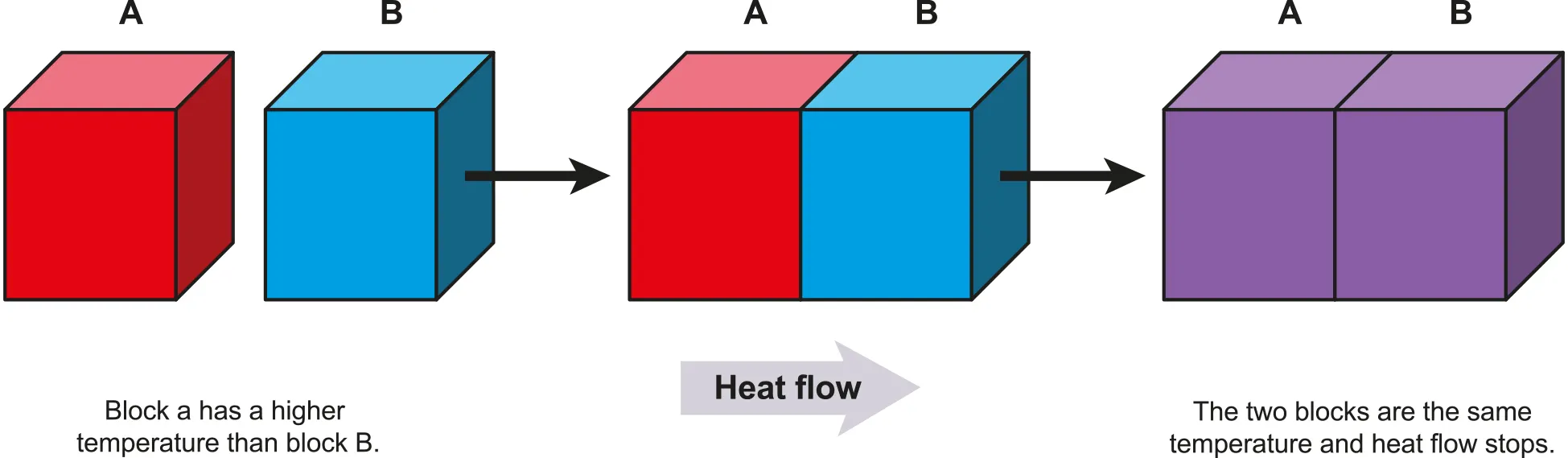

Substances at different temperatures will reach the same equilibrium temperature (Tf) such that the energy remains constant

•

Thermal energy usually only flows from high to low temperature

•

Heat flows from block A to block B since block A is at a higher temperature than block B

B.1.3-3 Diagram explaining contact thermal equilibrium

•

The molecules in A have higher KE on average than the molecules in B

•

When a molecule A with high KE collides with a molecule B with low KE, A will lose some of its KE and B will gain the same amount of KE.

◦

These collisions cause random KE to be transferred from block A to block B

◦

A greater temperature difference means there is a greater difference in the average KE and more KE being transferred by every collision

•

Heat (thermal energy) flows faster when the temperature difference is greater.

Conduction: Rate of thermal energy transfer through a solid

•

The rate of thermal energy transfer is:

◦

Proportional to the materials’ ability to conduct heat is referred to as its thermal conductivity

▪

Different materials transfer thermal energy at different rates

▪

Thermal insulators such as styrofoam transfer heat very slowly

▪

Metals such as copper transfer heat very rapidly

◦

Proportional to the surface area of contact

▪

Larger surface areas will transfer thermal energy faster

◦

Proportional to the temperature difference between the two surfaces

◦

Predictably larger temperature difference will have a greater rate of thermal energy transfer

◦

The rate of thermal energy transfer is zero if there is no temperature difference

◦

Inversely proportional to the thickness of the material.

▪

Thicker materials reduce the rate of thermal energy transfer

▪

In real life, thicker coats feel warmer, and houses with thicker walls (of the same material) are better insulated

◦

The temperature difference divided by the thickness x is often referred to as the temperature gradient

◦

Thus the equation for the rate of thermal energy transfer

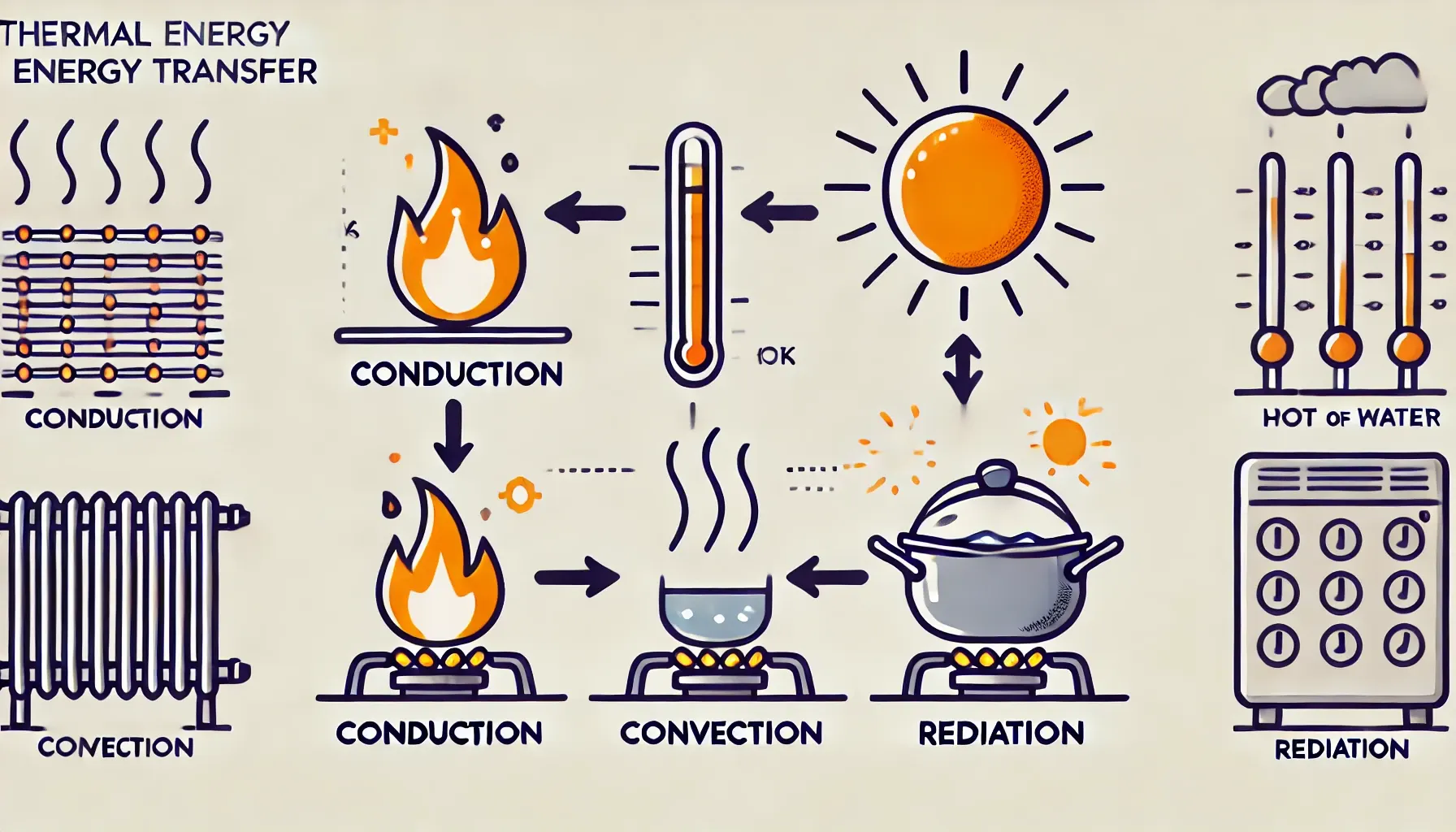

B.1.4 Convection

Convection: transfer of thermal energy through the ‘mixing of fluids’

•

When a fluid is exposed to a surface of higher temperature, the fluid in contact with the surface will increase in temperature and expand.

•

The higher temperature fluid will experience a change of density due to its thermal expansion and be forced upwards due to the buoyancy force.

•

The hotter fluid moving upwards and mixing with colder fluid causes a net transfer of thermal energy

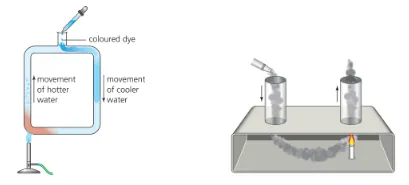

B.1.4-1

B.1.5 Thermal Radiation

Thermal Radiation

•

All the molecules in any object are constantly in motion, and the average random kinetic energy of the molecules is proportional to its temperature.

•

The molecules in the substance are constantly colliding with each other.

•

Each collision between molecules requires them to accelerate.

•

When the charges of the electrons and nuclei within the molecules are accelerated, they will release electromagnetic radiation (light waves).

◦

The wavelength and frequency of the waves depends on the magnitude of the acceleration.

◦

Collisions that require greater acceleration will produce electromagnetic waves of higher frequency.

◦

Since the velocity and direction of each molecule is random, the direction and frequency of the electromagnetic radiation is also random.

◦

Statistically if the average speed of the molecules is higher, the collisions will cause greater acceleration, and produce electromagnetic radiation of higher average frequency.

◦

As a result the kinetic energy of the molecules involved in a collision that emits electromagnetic radiation will decrease.

◦

On the other hand, molecules can also absorb electromagnetic radiation and as a result its kinetic energy will increase by exactly the same amount as the electromagnetic radiation it has absorbed.

•

The electromagnetic radiation emitted due to the random collision between the molecules of a substance is referred to as thermal radiation.

•

All objects emit thermal radiation, but the radiation of most objects at room temperature is in the infrared spectrum and is therefore invisible to human eyes.

•

At higher temperatures, the average frequency of the radiation emitted increases and starts to enter the visible spectrum as is the case of red-hot iron or fire.

Black-body radiation

•

Black body : works as both the perfect absorber and the perfect emitter of radiation

◦

It absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation

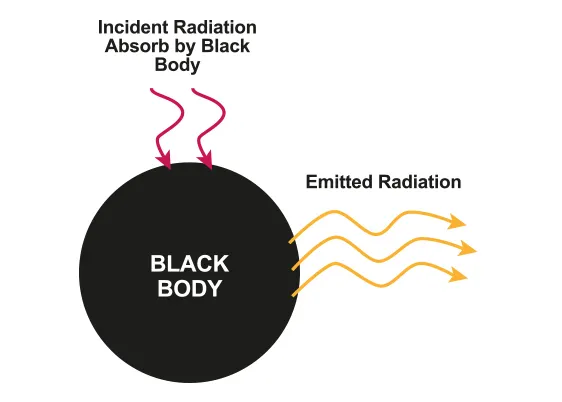

B.1.5-1 Diagram with incident radiation and emitted radiation of black body

•

The radiation emitted by a black body at constant temperature is called black-body radiation

•

Stefan-Boltzmann law: power of radiation emitted by a black body per unit area is proportional to the fourth power of its temperature

•

Black bodies are theoretically perfect emitters so therefore they have emissivity values of.

•

All other real objects only emit a fraction of the maximum power of thermal radiation black bodies can emit so they will have emissivity values of 1.

•

The two most well known approximations of ideal black bodies are:

◦

The opening of a hole (cavity) with an infinitely small opening.

▪

Only the opening is considered a black body because light going into the cavity will bounce around infinitely until it is absorbed

◦

Large, dense balls of ionized gas (stars).

▪

Stars are good approximations to a black body because their hot gasses are very opaque, that is, the stellar material is a very good absorber of radiation.

Thermal Equilibrium

•

Since objects at a higher temperature will emit thermal radiation at a higher rate, objects will tend to reach a temperature such that the power of thermal radiation emitted and the power of thermal radiation absorbed are equal.

•

Case 1: object in a room of different temperature

◦

Power of thermal radiation absorbed by an object:

▪

◦

Power of thermal radiation emitted by an object

▪

◦

At thermal equilibrium, the equilibrium temperature is:

▪

▪

▪

▪

Notice that the obvious conclusion that the temperatures of the room and the object need to be the same when they are in thermal equilibrium requires that the emissivity of the object is also used in the equation for the power of thermal radiation absorbed. In other more complex cases (such as planets) the power of thermal radiation absorbed by the object will not be the emissivity.

Wien's Law

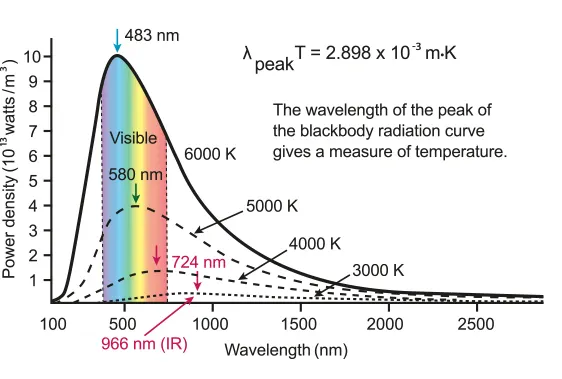

B.1.5-2 Graph that is showing the power density due to the wavelength

•

As seen in the graph, the wavelength of radiation emitted at a specific temperature is random, but some wavelengths are emitted at higher intensities.

◦

This is due to the fact that the velocities of the molecules are random, but the velocity of any particular molecule is more likely to be close to the average and less likely to be a lot slower or a lot faster.

•

As temperature increases the average random kinetic energy of the molecules increases

◦

This increases the number of collisions so more electromagnetic radiation is emitted

◦

The velocities of the molecules involved in collisions is higher on average which emits radiation of shorter wavelengths on average.

◦

The intensity of all wavelengths is greater

◦

The increase of the intensity of radiation emitted at shorter wavelengths is proportionally larger than the increase of the intensity of radiation at longer wavelengths

•

Notice that as the temperature increases the peak of the graph appears to move left.

◦

This means that most of the radiation is around the peak wavelength. It does not mean that all the radiation is at that wavelength.

◦

Other wavelengths are present but at lower intensities.

•

The temperature of the sun is around 5,770 Kelvin which means most of the thermal radiation is around the visible spectrum.

•

Objects at temperatures around room temperature radiate mostly in the infrared spectrum

B.1.6 Brightness and Luminosity

Luminosity: Power of thermal radiation of a star

•

Luminosity is calculated using Stephan-Boltzmann’s law

◦

Stars are assumed to behave like blackbodies so their emissivity is assumed to be equal to one,

◦

◦

The units of luminosity are the same units as power: watts

◦

Luminosity can also be express as a multiple of the luminosity of our sun

◦

Brightness: observed intensity of a star as seen from earth

•

Intensity is defined as the power (in the case of a star, its luminosity) of a wave over the total area the wave is spread over.

•

As light from a star travels away from the star, it spread out in a spherical shape which makes the area

•

This makes the brightness of a star