Understanding points

Understanding points

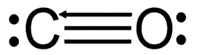

Structure 2.2.1—A covalent bond is formed by the electrostatic attraction between a shared pair of electrons and the positively charged nuclei.

Structure 2.2.2—Single, double and triple bonds involve one, two and three shared pairs of

electrons respectively.

Structure 2.2.3—A coordination bond is a covalent bond in which both the electrons of the shared pair originate from the same atom.

Structure 2.2.4—The valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) model enables the shapes of

molecules to be predicted from the repulsion of electron domains around a central atom.

Structure 2.2.5—Bond polarity results from the difference in electronegativities of the bonded

atoms.

Structure 2.2.6—Molecular polarity depends on both bond polarity and molecular geometry.

Structure 2.2.7—Carbon and silicon form covalent network structures.

Structure 2.2.8—The nature of the force that exists between molecules is determined by the size

and polarity of the molecules. Intermolecular forces include London (dispersion), dipole-induced

dipole, dipole–dipole and hydrogen bonding.

Structure 2.2.9—Given comparable molar mass, the relative strengths of intermolecular forces are generally: London (dispersion) forces < dipole–dipole forces < hydrogen bonding.

Structure 2.2.10—Chromatography is a technique used to separate the components of a mixture

based on their relative attractions involving intermolecular forces to mobile and stationary phases. |

Covalent bond

•

Sharing of electron pair(s) between two atoms and resulting electrostatic attraction between (-ve) shared electron pair(s) and (+ve) two bonding nuclei

Bond order | Example | Electrons involved | |

Single bond | 1 | F-F, C-C | 2 |

Double bond | 2 | O=O, C=C | 4 |

Triple bond | 3 | N≡N, C≡C | 6 |

Comparison of bond length and strength

•

Bond length: distance between 2 bonded nuclei

◦

Single > double > triple

•

Bond Strength/Enthalpy: energy required to break the bond

◦

Single < double < triple

•

∵ greater attractive force between the nuclei as bond order increases

3 steps to identify carbon-carbon bond type

1.

Identify no. of H for each C

2.

Calculate no. of e- for C to C bond (4 - no. H)

3.

If 1 e-, single like C2H6 / 2 e-s, double ike C2H4 / 3 e-s, triple like C2H2

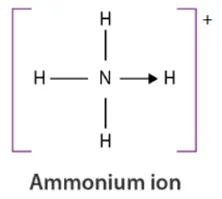

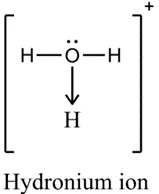

Coordination bond: electron pair(s) in the bond come from one atom

•

If using single line not dot and cross, a headed arrow needs to be drawn

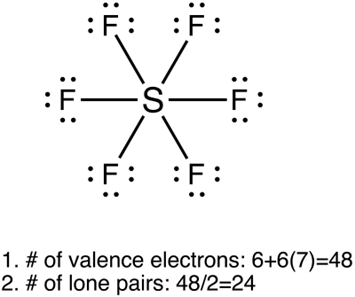

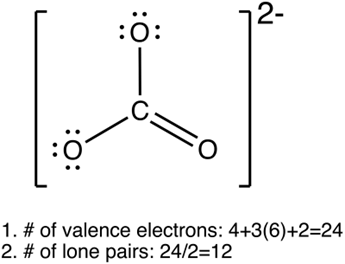

Lewis structure

•

“dots and crosses representation of valence shell electrons of atoms in a molecule”

1.

Calculate total no. of valence e-s in the molecule

•

Tip: divide the total no.of valence e-s by 2 to find the no.of lone pairs

1.

Draw single bonds to the central atom

2.

Put all remaining valence electrons as lone pairs

3.

Turn the lone pairs into double/triple bonds to give every atom an octet

•

exceptions to the octet rule → H: 2e-, Be: 4e-, B&Al: 6e-

◦

e.g. BeCl2, BH3, BF3

◦

e- deficiency leads to tendency to be coordination bond: NH3BF3

•

If central atom is P,S,Cl additional e- can be added → P&S: 8e-, 10e-, 12e- Cl: 8e-,10e-,12e-,14e-

•

If molecule is charged e.g. OH-

1.

When calculating no. of valence e-s, add 1 e- for each -ve, subtract 1 e- for each +ve charge

2.

Square bracket with overall charge

Figure 4.3.1 Lewis structures of SF6 and CO32-. Line represents a pair of electrons

VSEPR - Valence-Shell Electron-Pair Repulsion Theory

•

Pairs of electrons arrange themselves around the central atom so that they are as far apart from each other as possible

•

Electron domain = 1, 2, 3 e- pair

•

If no. of e- domain ≠ no. of bonding pairs, electron domain geometry ≠ molecular geometry

•

Repulsion strength of lone pair is greater than bonding pair → bond angle is reduced

Electron Domain | Bonding | Lone pairs | Molecular Geometry | Bond Angle (o) | Chemical Structure

(+ example) |

2 | 2 | 0 | Linear | 180 | CO2 |

3 | 3 | 0 | Trigonal Planar | 120 | BF3 |

2 | 1 | Bent, V-shaped | 117.5 | BF2-, SO2- | |

4 | 4 | 0 | Tetrahedral | 109.5 | NH4+ |

3 | 1 | Trigonal

Pyramidal | 107 | NH3, PCl3 | |

2 | 2 | Bent, V-shaped | 104.5 | NH2-, H2O | |

5 | 5 | 0 | Trigonal Bipyramidal | 90

120 | PCl5 |

6 | 6 | 0 | Octahedral (square bipyramidal) | 90 | SF6, ICl6+ |

Bond polarity

•

Polarity = Partial charge → represented by delta (ẟ+, ẟ+-)

•

Due to unequal sharing of electrons in a bond → represented by a vector

•

More electronegative atom exerts a stronger pull on the electrons

H-F | H-Cl | H-Br | H-I | H-H | |

Δ electronegativity | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

Bond polarity | More Polar | ← | ← | Less polar | 0 (Non-Polar) |

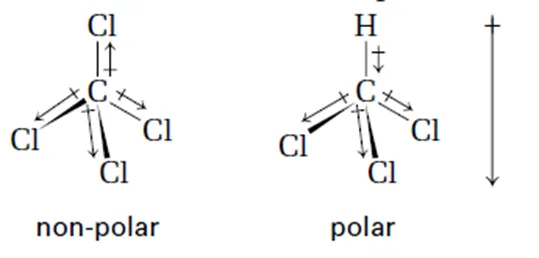

Molecular polarity

•

Depends on both bond polarity and molecular geometry

•

Nonpolar bonds → nonpolar molecule

•

Polar bonds → net dipole must be zero for molecule to be nonpolar

Covalent network structures

1.

Allotropes of Carbon

•

Allotrope: different forms of an element (in same physical state), e.g. O2 and O3

Allotrope | Graphite | Diamond | Fullerene C60 | Graphene |

Hybridisation/ bond angle | sp2/ 120oC | sp3/ 109.5oC | sp2/ <120oC | sp2/ 120oC |

Carbon atoms | Each C atom attached to 3 others by sigma bond | Each C atom attached to 4 others by sigma bond | Each C atom attached to 3 others by sigma bond | Each C atom attached to 3 others by sigma bond |

Structure | Hexagon layers held by van der waals | Giant covalent structure - tetrahedron | Spherical cage formed by atoms arranged as pentagons and hexagons | Single hexagonal layer |

Solubility | Poor in both polar and non-polar solvent | |||

Electrical conductivity | Poor/none when molten | |||

V good because of delocalised e- (one e-/C atom) | Poor because of no delocalised e- | Semiconductor due to some e- delocalisation & mobility | V good because of delocalised e- (one e-/C atom) | |

Usage | Pencil

Electrode rods | Used industrially in drills + polishing tools | Lubricant

Drug targeted delivery vehicle | Touch screen (bendable) |

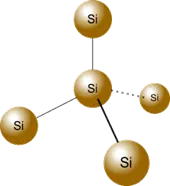

2.

Silicon & Silicon dioxide

Si | SiO2 |

Silicon atoms are arranged in the same way as the carbon atoms are in diamond, however silicon:

- Does not show allotropic behaviour

- Is weaker than diamond

| Each silicon is bonded to 4 oxygen/ each oxygen bonded to 2 silicon/ ratio of Si and O is 1:2

strong

insoluble in water

high melting point

non-conductor of electricity |

Intermolecular forces

•

Polar = partially +ve, -ve

•

Dipole (moment) = direction of polarity (one end partially -ve, another end partially +ve)

•

‘Van der Waals’ force is a collective term that includes London + dipole-dipole forces

Type | London dispersion | Dipole dipole | Dipole-induced dipole | Hydrogen bond |

Explanation | Electrostatic attraction b/w | |||

non-polar molecules with temporary induced dipoles (due to random shift in e- position) | polar molecules with permanent dipoles | Polar molecules and nonpolar molecules | polar molecules with permanent dipoles where H is bonded to [F, O, N] | |

Strength | ∝ molecular size/ no. of e- | ∝ electronegativity difference value upto 1.8 (polarity) | Stronger than London, weaker than dipole-dipole | ∝ no. of H bonds that can form |

Example | Ethane, Br-Br | Ethanal, H-I | H2O, O2 | Ethanol, H2O |

Strength: London (dispersion) < dipole-induced dipole < dipole–dipole < hydrogen bonding

Solubility of molecules in water

•

Solute molecules break intra/intermolecular bonds and form bonds intermolecular bonds (forces) with solvent molecules ˙.˙ energetically more favourable

•

general rule: like dissolves like → polar will dissolve polar, non-polar will dissolve non-polar

1.

Intra for ionic compounds

2.

Inter for simple covalents

3.

Giant covalents are not soluble

Solvent | Polar (e.g. water) | Non-polar (e.g. hexane) |

Solubility | ∝ polarity | ∝ 1/polarity |

Explanation | H-bondable solutes are most soluble | Strongest london dispersion force forming solutes are most soluble |

Example | MgO > NaCl > C2H5OH > CH3COOH | Br2 > CCl4 > CH3COCH3 > |

Ethanoic acid vs propan-1-ol (boiling point)

•

Both have the same molecular mass but

•

Alcohols have higher b.p. than hydrocarbon of the same RMM ˙.˙ of H-bond.

•

Carboxylic acid higher b.p. Than alcohol of the same RMM ˙.˙ of dimerisation

•

Dimerisation increases RMM (to 120) and van der waal’s

•

H-bond > van der waal’s but van der waal’s of large hydrocarbon also very strong, e.g. nonane, C9H20 (RMM = 118), has b.p. of ~150oC

•

Carboxylic acid ‘s h-bond is reduced due to dimerisation but gains van der waals’ force of equivalent strength to nonane

Ethanoic acid | Propan-1-ol | |

B.P. | 118oC | ~98oC |

Physical properties of (ionic/covalent) compounds

Giant covalent | Ionic | Metal | Simple covalent | |||

Intra vs Inter | Intramolecular | Intermolecular | ||||

Polar covalent | Non-polar covalent | |||||

Bond | Covalent | Ionic | Metallic | Hydrogen bond | Dipole-dipole | London dispersion |

IMF Strength | Strong ← Weak | |||||

B.P. (M.P.) | Diamond

(3600 °C) | CaO

(2,572 oC) | Al

(660 °C) | C2H5OH

78 °C | C2H5Cl

12 °C | C2H6

-89 °C |

Electrical conductivity (solid) | Partial | No | Yes | None | ||

Electrical conductivity (molten) | No | Yes | No | None | ||

Electrical conductivity

(aqueous) | No | Yes | No | Partial (polar covalent may ionize to conduct electricity, e.g. H2O -> H3O+ + OH-) | ||

Solubility (polar) | none | More Soluble ← Less Soluble

(except for metals) | Insoluble | |||

Solubility (non-polar) | Insoluble | Less Soluble → More Soluble

(hydrocarbon part within polar covalent molecule may allow some solubility) |

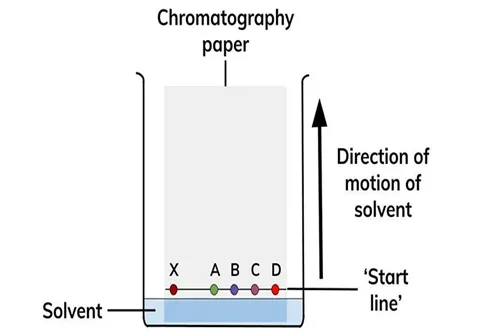

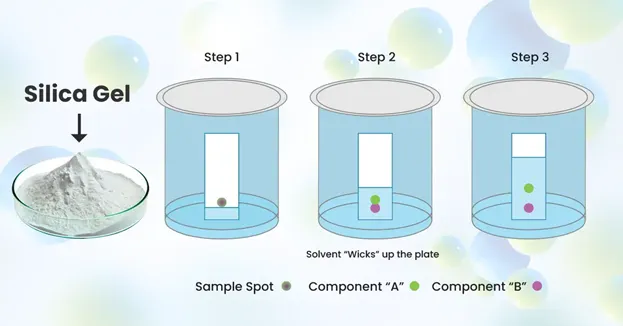

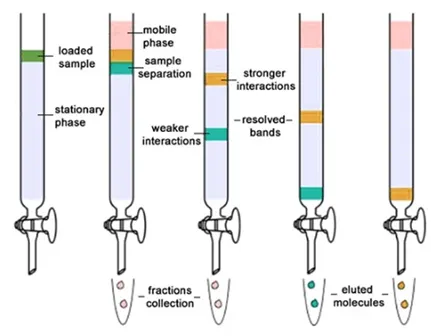

Chromatography

•

Separation of mixtures based on their affinities for the mobile and stationary phase

•

Affinities involve intermolecular forces

Paper

More soluble components move farther up the paper

Retardation factor Rf = distance traveled by solute / distance traveled by solvent

Thin layer

Alumina (Al2O3), silica (SiO2) as stationary phase

Liquid column

Solvent poured down the column

Components in the mixture separate into bands